Four days remain. Halloween has passed, and I find myself on vacation, waiting for a night of feasting, merriment and memories with my family. As I crave for turkey and dressing, my mind wanders to the days of OHR yore, when I entered a Halloween contest nearly out of spite for the concept. The game that won was my own, Thanksgiving Quest. It had nothing to do with ghosts, pumpkins, or paganism, but had such a commanding gameplay concept that players opted to select it as the best of show, like a blue ribbon-earning hog at a country fair.

We're contest junkies in this community, make no mistake. Nearly every active developer for the engine has entered a contest in the hopes of gaining that fabled 15 seconds of fame or whatever meager prize is being offered, and never delivered upon on some occasions. But it's pretty rare that any of us get one of our games right, much less respond correctly to the contest's theme. Thanksgiving Quest arguably succeeded on the design front, but made no attempt to even reference Halloween beyond the obvious Halloween Quest title rip-off. Interestingly, Halloween Quest is nearly the opposite—a game that is vanilla in almost all respects, but does a commendable job fitting the holiday bill.

Why is it that we so rarely get both of these right? What is so difficult about making a game that is both solid and fits with the contest it has been entered in? It could very well be that most authors enter the contest with only one of these goals in mind. I would wager RedMaverickZero intended to win the Halloween contest, and made every effort to have his game satisfy the restrictions. My game's design was drawn out a month prior to the contest, and the game was not even originally going to be entered, but when the opportunity presented itself I tried to slap on a Halloween theme, instead opting to take a parody route.

The 2009 Halloween contest announcement thread contains a back-and-forth argument about the potential of the OHRRPGCE to frighten its players. We have some OHR games developed in the horror genre, but they are uniformly not frightening as a result of their mechanics. Bloodlust, for instance, shocks its player with such images as a flying vagina monster. Pitch Black makes a giant gargoyle statue appear suddenly. In every horror game I have played on the engine, the ability to scare comes not from the engine's strengths or the medium of video games, but the game creator's artistic skill.

I had a discussion not too long ago with a non-gamer regarding that wondrous topic we know so well: “Are video games art?” Without delving too much in to the particulars of said conversation, my friend made an interesting point. In his mind, the things that most “artistic” video games have accomplished are merely implementations of other artistic mediums. In some ways the video game is the most post-modern form of expression available to us today, as it is essentially a hodge-podge of film, visual arts, music and literature with interactivity thrown in the mix.

Shadow of the Colossus, often toted as one of the most artistic games created in the past ten years, impresses us more with its stunning visual scope and feeling of isolation, both of which can directly be attributed to film influence. Other recent games such as Bioshock, Metal Gear Solid 2, Okami, and Final Fantasy X clearly owe their power of expression to existing mediums. I have difficulty arguing against my friend in each of these cases; it is clear to me that only an avid gamer would be able to construe an artistic quality unique to the video game in every example.

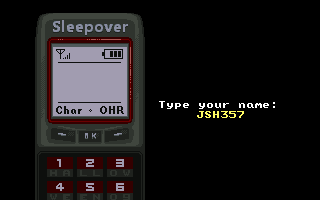

This brings us to Charbile's 2009 title, Sleepover. It is a fascinating little acid trip of a game, and spoiling every neat little detail about it in a review would be pointless and lessen its impact. In short, the game is basically an interactive retelling of John Barth's short story, “Lost in the Funhouse,” in which he takes his protagonists on a trip through the recesses of the medium of literature; similarly, Charbile's game takes the player through a creepy envisioning of OHR game development. What I find quite redeemable and exciting about this game is that it shows, in perhaps some dark recess of his mind, Charbile recognizes the power of a video game to express itself, dare I say artistically, in some emergent “solid chunk” of post-modern shock value. To put it more simply, games only mean something when they do.

I have the feeling that if I asked my mother to play Sleepover, she would not understand it in the least, not find anything about it frightening, and probably wonder what I had been smoking before suggesting she waste her time. If you have played the game, then you know: Sleepover's intended audience is slim. It is a game made by a veteran OHRRPGCE developer for veteran OHRRPGCE developers. Nobody else is going to get it, and Charbile recognizes this. Instead of bemoaning that fact, he emphasizes it, and in doing so toys and creates with one of the engine's most unusual features: its community.

We try to run away from the idea, but it is very true that most OHR games are only going to be played by the denizens of Slime Salad and Castle Paradox. Over time, this community has become so ingrained in the engine's history that a wide span of games have emerged clearly intended only for this small set of people. Experimental one-shots, joke games, community movies, and collaboration games all fall in to this category.

The internet has influenced humanity's artistic taste more steeply than some of us realize. Who would have thought fifty years ago that people would watch crappy videos on Youtube and enjoy them? Almost everybody these days has a Facebook, Myspace, or Livejournal page where they post “works of art” such as journal entries, photographs, and podcasts. Large message boards such as GameFAQs, Something Awful, and 4chan have produced a wide variety of “web memes” that have approximately the same lasting appeal as pop culture references.

It is my observation that the OHRRPGCE's library of games, more often than not, falls in to this range of media. The work is not intended to be high art, nor should it be, and instead has personal significance to one or more users. Think about how many of your friends' Facebook updates actually stick in your mind for more than ten seconds. Done counting? Like it or not, that is the way most of us play (or do not play) OHRRPGCE games. This does not mean that OHR games have no value, but it does mean that the value they possess is restricted.

At the very end of Sleepover, the author states that he is joking about the game's content and clear criticism of the OHRRPGCE's community and shortcomings. His words immediately reminded me of Mark Twain's famous opening to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which blatantly states that anybody seeking a moral in his work deserves to be shot. Naturally, this is a form of reverse psychology, and it is the same trick Charbile manages to pull off in his game.

I can state with a fair amount of confidence that any older OHR user who actually plays and understands Sleepover will escape the program thinking about where he is going and where he has been. The protagonist, effectively named after the player with a clever Earthbound reference, has found himself trapped in a dystopian recreation of the OHR community, and escapes only to find mockery. The fact that Charbile makes an OHR game to express the psychological effect of making one is chillingly appropriate; we see ourselves in every facet of this game. Charbile could be referencing one of his own experiences with making OHR games (and he has to be) or he could be referencing what he has seen happen with hundreds of other developers.

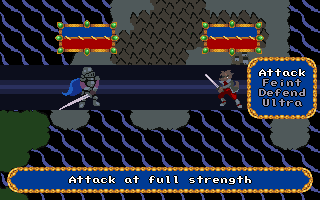

In any case, Sleepover is one of the few OHR games that has stepped on to the threshold of making an artistic expression using something specific to the engine. For that achievement, it is my choice for the winner of the 2009 Halloween contest, certainly one of the most fascinating OHR games ever developed, and ultimately just a great game to think about. There are other aspects of the game worthy of discussing, such as Charbile's creation of several battle engines, references to other OHR games, and creative use of slices, but all of those essentially end up being cosmetic.

Oh, also it looks cool and has funny music; here are some numbers: Graphics 8, Sound 9, Writing 7, Mechanics 5, Overall 8. Happy Thanksgiving, everyone!